It is often said that Nichiren’s Buddhism begins and ends with his great treatise 'On Establishing The Correct Teaching For The Peace Of The Land'. Eddy Canfor-Dumas offers some thoughts on its relevance today, especially to those practising Buddhism within the SGI.

A historical perspective

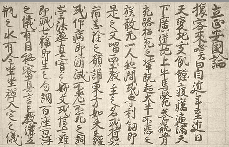

Nichiren submitted On Establishing The Correct Teaching For The Peace Of The Land in July 1260 to Hojo Tokiyori, the effective ruler of Japan, as a warning that the nation must turn away from erroneous Buddhist teachings and embrace the Lotus Sutra. If it did not, he said, the disasters it was then experiencing would continue and worsen. Specifically, he warned that Japan would suffer both internal revolt and foreign invasion, the only two of the seven disasters predicted in key Buddhist texts for countries that ‘slander the Law’, which had yet to materialise.

In submitting On Establishing The Correct Teaching Nichiren was following an instruction found in the Lotus Sutra itself about its propagation in the time after the Buddha Shakyamuni’s death – ‘After I have passed into extinction, in the last five hundred year period you must spread it [this sutra] abroad widely (kosen-rufu) throughout Jambudvipa and never allow it to be cut off’ (Lotus Sutra, Ch.23). In other words, kosen-rufu and establishing the correct teaching are one and the same.

Despite this and other clear textual proof from the sutras, for his efforts Nichiren was subjected to a series of persecutions over many years. Establishing the correct teaching involves challenging incomplete teachings and his criticisms enraged the other Buddhist schools then dominant in Japan, and their powerful political backers. Their hostility culminated in the attempt to behead him at Tatsunokuchi in 1271 and his subsequent exile to Sado Island, where he was expected to die.

The following year, however, his prediction of internal revolt came true when there was an attempted coup within the ruling clan; and his prediction of foreign invasion was borne out when the Mongols attacked Japan in 1274 (and again in 1281). For many people these events proved his status as a ‘sage’ – someone who fully understands past, present and future – and prompted the ruling authorities to pardon him from exile.

Even so, his remedy for the ills of the age – to withdraw support from Buddhist schools based on incomplete teachings and embrace the practice of the Lotus Sutra as the foundation of a peaceful society – was still ignored.

In fact, it wasn’t until many centuries later and another foreign invasion of Japan (this time successful), that the Soka Gakkai appeared in 1945 to establish the teachings of Nichiren, first in Japan and then around the world.

It is no surprise that, as with Nichiren, the organisation has met fierce opposition from various secular and religious authorities. Its forerunner, the Soka Kyoiku Gakkai, was outlawed by the militarist government (and abandoned by the Nichiren Shoshu priesthood) in the run-up to the Second World War. Its founder, Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, and his closest disciple, Josei Toda, were both put in prison, where Makiguchi died. And Toda’s successor as president of the Soka Gakkai, Daisaku Ikeda, has had to endure decades of criticism in the Japanese media, as well as the hostile actions of Nichiren Shoshu priests and their allies.

So why has On Establishing The Correct Teaching inspired such selfless dedication, and also such vehement opposition, for more than 750 years?

The answer is that this treatise, the Buddhist doctrine on which it is based and the organisation it has inspired, aims at no less a goal than the fundamental, positive and permanent transformation of human life and society, and its relationship to the natural world. As the 'Preamble To The Rules And Regulations Of The Soka Gakkai' states:

The spirit of the oneness of mentor and disciple, and the selfless practice of propagating the Law for the attainment of kosen-rufu, both embodied in the lives of the ‘Three Successive Presidents’ is the core of the ‘Spirit of the Soka Gakkai’. Herein lies our eternal guiding model. The Soka Gakkai, rooted in the spirit of Buddhist compassion, shall be dedicated to realising world peace and happiness for all humanity.

This is a hugely ambitious goal and, as Nichiren says, ‘good by the inch invites evil by the foot’ – that is, Buddhahood stirs up fundamental darkness.

But what evidence is there that practising the Lotus Sutra – specifically, chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo – is the ‘correct teaching’? How will establishing it lead to the ‘peace of the land’? And what exactly does ‘establishing’ it mean, anyway?

All of these questions have prompted intense debate and controversy from the moment in 1253 that Nichiren declared Nam-myoho-renge-kyo to be the correct teaching for this age.

The correct teaching

Nichiren based his conclusion on an exhaustive study of Buddhist texts that revealed teachings of varied profundity. However, all are flawed in some way. Some deny enlightenment to certain categories of people – to women, for example. Others teach enlightenment as, effectively, an unattainable ideal. And still others teach that it can be achieved only after rebirth in a kind of Buddhist paradise. Only the Lotus Sutra teaches that the highest state of life – Buddhahood – is attainable by all people, here and now in this present world of often harsh reality.

But even the Lotus Sutra is limited, as it doesn’t teach a practical means for ordinary people to reveal and develop their Buddhahood.

Nichiren remedied this by teaching that faith in, practice to and study of the Dai-Gohonzon of the Three Great Secret Laws will enable anyone to attain Buddhahood in this lifetime. This, says Nichiren, is the correct teaching:

Believe in the Gohonzon, the supreme object of devotion in all of Jambudvipa. Be sure to strengthen your faith, and receive the protection of Shakyamuni, Many Treasures, and the Buddhas of the ten directions. Exert yourself in the two ways of practice and study. Without practice and study, there can be no Buddhism. You must not only persevere yourself; you must also teach others. Both practice and study arise from faith. Teach others to the best of your ability, even if it is only a single sentence or phrase… I have herein committed to writing the doctrines of my own enlightenment (Writings of Nichiren Daishonin Vol.1, pp386-7).

It is this doctrine that he devoted his life to propagating and for which he suffered extraordinary persecution. And although at the time of writing On Establishing The Correct Teaching he had not yet begun to inscribe the Gohonzon, this is essentially the doctrine he (as the Host in the narrative) urges on Hojo Tokiyori (as the Guest). The key passage states:

Therefore, you must quickly reform the tenets that you hold in your heart and embrace the one true vehicle, the single good doctrine [of the Lotus Sutra]. If you do so, then the threefold world will become the Buddha land, and how could a Buddha land ever decline? The regions in the ten directions will all become treasure realms, and how could a treasure realm ever suffer harm? (WND-1, p25)

That is, when the Buddha nature of the Guest is revealed through practising the correct teaching, his environment will be transformed into a Buddha land that reflects his highest life condition. This transformation, based on the principle of the oneness of life and its environment, is at the heart of ‘establishing the correct teaching for the peace of the land’.

Understanding ‘the land’

In this instance, ‘the land’ is the personal environment of the individual, wherever he or she might be, and in whatever circumstances. The more individuals who embrace ‘the single good doctrine’, the more these Buddha lands will overlap, merge and bring about a positive transformation of our shared social and physical environments – the ‘land’ of our towns, cities, countries and, ultimately, our world.

The principle of establishing the correct teaching is therefore essentially democratic. As evidence of this, in On Establishing The Correct Teaching Nichiren uses three different ideographs for the word ‘land’. One represents a king within his domain; a second represents a weapon within the domain; and a third represents people in a domain. This third ideograph is used about eighty per cent of the time for ‘land’.

In other words, the correct teaching is not established by converting the ruling elite or by force of arms, but is established in the hearts of ordinary people, one after another. In this sense, ‘the peace of the land’ also has much in common with the modern concept of human – as opposed to military or national – security.

During the 1930s, however, Japanese militarists, in collusion with various Nichiren schools (including Nichiren Shoshu), deliberately perverted this use of the word ‘land’ to refer only to Japan. Their goal was to unite all elements of society – religious and secular – in a nationalistic drive, based on State Shinto, for imperial expansion and war.

As Ikeda notes, this was wholly contrary to Nichiren’s message: ‘On Establishing The Correct Teaching concludes with the Daishonin’s warning against war, the absolute worst of all man-made disasters’ (World of Nichiren Daishonin's Writings, Vol 1, p. 107).

What does ‘establish’ mean?

Neither is it correct to conclude that establishing the correct teaching means to make Nichiren Buddhism the state religion of Japan or any other country; in fact, following his pardon from exile Nichiren refused a government offer to establish a temple for his school. The demand he makes in On Establishing The Correct Teaching is simply that support at all levels be withdrawn from incomplete Buddhist doctrines:

Now if all the four kinds of Buddhists within the four seas and the ten thousand lands would only cease giving alms to wicked priests and instead all come over to the side of the good, then how could any more troubles rise to plague us, or disasters come to confront us? (WND-1, p23)

In other words, monks, nuns, laymen and laywomen – i.e. all people – should freely choose to transfer their support to the Lotus Sutra.

Seen in this light, the concept of the fusion of Buddhist Law and secular rule (obutsu myogo - see Miyaki p. 69) should not be confused with the Islamic concept of sharia, where the laws of the land are a direct expression of religious doctrine. Rather, it describes how the compassionate spirit of the Lotus Sutra can come to influence positively all sections of society and help to transform social problems.

Moreover, while Nichiren’s goal of establishing the correct teaching is fundamentally democratic, not everyone needs to embrace his teachings for the peace of the land to be secured. According to Toda, the transformation will come about when roughly a third of the population chooses to practise Nichiren Buddhism:

Suppose the movement for kosen-rufu continues to make rapid progress, with the membership increasing at an ever-accelerating rate. Eventually about one-third of the population will have started practising true Buddhism, just as one-third of the citizens of Shravasti embraced Shakyamuni’s teaching. At that time the Soka Gakkai will have spread to all fields of society, producing many talented people in every area. The Soka Gakkai will then have become not only a magnificent parent organisation for educating and enlightening people, but also an indispensable nucleus for the peace and culture of all humankind (Ikeda, The Human Revolution, Vol. 10).

In this sense, therefore, ‘establishing the peace of the land’ is achieved by directly converting a significant number of people to the practice of Nichiren Buddhism.

Propagation in contemporary society

There is also an indirect and complementary process, however, as Ikeda explains:

The Soka Gakkai promotes correct faith in order to establish the correct teaching on the level of the individual. To do so on the level of society, we are spreading the spirit to respect human beings and put people first. Based on these ideas, we are advancing a movement for peace, culture and education in actual society – in other words, in the secular realm. (World of Nichiren Daishonin's Writings, Vol 1 p. 85)

Ikeda established this movement – in the face of much disagreement – when he became third president of the Soka Gakkai:

The holding of culture festivals, the formation of the fife-and-drum corps, the building of training centres – each of these initiatives was met with widespread opposition! To help more people understand the wonder of Buddhism, we need to create a ‘universal forum’ of culture, education and peace (The Wisdom of the Lotus Sutra, Vol 5, p. 37).

Elsewhere, Ikeda explains that this movement in the secular realm is firmly based on principles derived from the Lotus Sutra; specifically, on the function of the bodhisattvas of the theoretical teaching as outlined (paradoxically) in the final six chapters of the sutra, during ‘the second assembly at Eagle Peak’. He says:

The bodhisattvas [of the theoretical teaching], believing in and accepting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo contained in the depths of the ‘Life Span’ chapter, show actual proof of the Mystic Law in their respective fields of endeavour. They each test and prove, and then propagate the Mystic Law. (Ibid., Vol 6, p. 8).

…It is a two-way process. Through this cycle of practising faith and taking action in society, we can realise boundless growth in our lives and limitlessly advance kosen-rufu… The SGI’s fundamental path of promoting peace, culture and education based on Buddhism has its origin in the principle of this second assembly at Eagle Peak. We are advancing just as the Lotus Sutra teaches (Ibid., Vol 6, pp. 11-12).

The individual paths of peace, education and culture are also themselves based on elements found in the ‘Life Span of the Thus Come One’ (sixteenth) chapter of the Lotus Sutra, namely the virtues of (respectively) sovereign, teacher and parent:

Broadly speaking, creating a land of peace and tranquillity – as in the passage, ‘This, my land, remains safe and tranquil’ – indicates the virtue of the sovereign. Education represents the virtue of the teacher. And culture, because it cultivates and fosters people’s inner lives, relates to the virtue of the parent. We are extending this path of the Three Virtues throughout the entire world. (Learning from the Gosho, pp. 63-4)

While based on the Lotus Sutra, the three elements of this path also arise from Ikeda’s understanding of the historical roots of the Soka Gakkai. He says:

The soka of Soka Gakkai means ‘value creation’. War, which destroys everything in its path and robs people of their precious lives, is the most barbarous of acts and is an activity of the greatest ‘anti-value’. That is why first Soka Gakkai president Tsunesaburo Makiguchi fought against Japan’s militarist government, was imprisoned, and died in jail for his beliefs. We, his successors, have inherited this spirit and aspire to create lasting peace.

Education which fosters humane individuals is the foundation of value creation. This was one of the reasons why the Soka Gakkai originally started out as the Soka Kyoiku Gakkai (Value-Creating Education Society) and its membership was comprised mainly of educators. When value is created it comes to bloom as culture, which in turn nourishes and enriches society. In this respect, promoting activities for peace, education and culture is the social mission of the Soka Gakkai, which bases itself on the humanistic philosophy of Buddhism (NL 4474).

If the 'Preamble To The Rules And Regulations' sets out the religious mission of the Soka Gakkai and the SGI, the SGI Charter sets out this social mission. The Charter stresses the goals of the SGI in society and so refers only obliquely to its religious mission – ‘SGI shall promote an understanding of Nichiren Daishonin’s Buddhism through grass-roots exchange, thereby contributing to individual happiness.’

This twin-track approach to establishing the correct teaching – religious and secular – has been pursued consistently by Ikeda since becoming third president. While teaching others about Nichiren’s Buddhism through continually lecturing and writing on the Gosho, the Lotus Sutra and various Buddhist commentaries, he has also penned many works which, while inspired by Buddhist thought, are not explicitly Buddhist in content.

In addition, he’s held dialogues with a wide range of scholars, artists and political leaders, all with a view to broadening the world’s understanding of the SGI – and SGI’s understanding of the world.

Ikeda has not only spoken and written; he’s also taken action. He has personally helped broker understanding between China and Japan, and between China and Russia, the latter at a time of great international tension. He’s organised campaigns against nuclear weapons, established educational, cultural and peace institutes and, alongside Toda, set up Komeito, which is now a significant player in Japanese politics (though no longer linked directly to Soka Gakkai).

As Nichiren says, ‘A person of wisdom is not one who practises Buddhism apart from worldly affairs but, rather, one who thoroughly understands the principles by which the world is governed’ (WND-1, p1121)

In short, Ikeda has both explained and demonstrated how the movement to establish the correct teaching for the peace of the land can advance along these complementary paths in the twenty-first century.

To neglect to develop either path - especially Ikeda's ‘universal forum’ of culture, education and peace - would be to hamper that movement.

Read Daisaku Ikeda's essay On Nichiren