Frank O. Gehry has been called the most famous

architect on earth, the most important architect of the twenty-first century, a

legend and a superstar. Oh, and he’s

been on The Simpsons, the ultimate barometer of fame, writes Geraldine

Royds

Frank O. Gehry has been called the most famous

architect on earth, the most important architect of the twenty-first century, a

legend and a superstar. Oh, and he’s

been on The Simpsons, the ultimate barometer of fame, writes Geraldine

Royds

The architect’s daring buildings have revitalized urban spaces and his buildings are recognized as among the most profound and brilliant works of architecture of our time. Not bad for a man who says of himself, ‘I'm only an architect, no matter what anybody says - a humble architect.’

Frank O. Gehry was born in Toronto, Canada, in 1929. He moved with his family to Los Angeles as a teenager and studied architecture at the University of Southern California. He worked for other architects, served in the US Army, studied city planning at Harvard, lived in Paris, and eventually went back to California, where he started his own design firm in 1962.

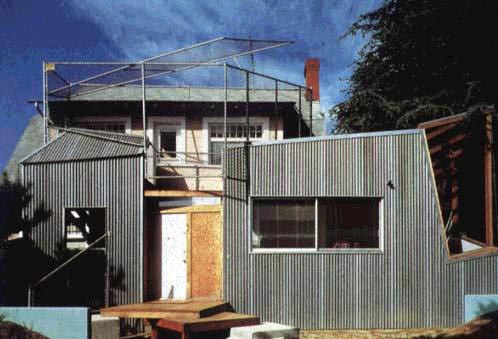

By the 70’s, he was hanging out with a group of innovative artists in the beach community of Venice, who were finding new uses for industrial materials. Gehry began using materials such as unpainted plywood, rough concrete, and corrugated metal in his own work.

Although he had

had his first brush with fame with a line of corrugated cardboard furniture and

he had built imaginative houses for some of his artist friends, it wasn’t until

1978, after more than twenty years in the business, that he finally got

international recognition for one of his buildings – his own home. He reworked the architecture in the most

radical way. Leaving the original house intact, he encased it in a shell made

from metal, chain-link fencing, and glass, transforming the conventional pink

bungalow into a piece of installation art. His neighbours didn’t like it and

threatened to take him to court - but architectural students began to come from

all over the world to see it.

He reworked the architecture in the most

radical way. Leaving the original house intact, he encased it in a shell made

from metal, chain-link fencing, and glass, transforming the conventional pink

bungalow into a piece of installation art. His neighbours didn’t like it and

threatened to take him to court - but architectural students began to come from

all over the world to see it.

Many of his corporate clients were unhappy about the experimental building too and his business suffered although others praised his vision. Richard Koshalek, head of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, said ‘Frank understands space; many architects don't. He uses common materials like an artist, with elegance.’

Gehry continued to use imaginative elements in his work and he went on to design a string of houses, offices and museums. Critics talked about his ability to explode and reassemble geometric shapes, a practice they dubbed "deconstructivism”. His work was admired for its vividness and audacity.

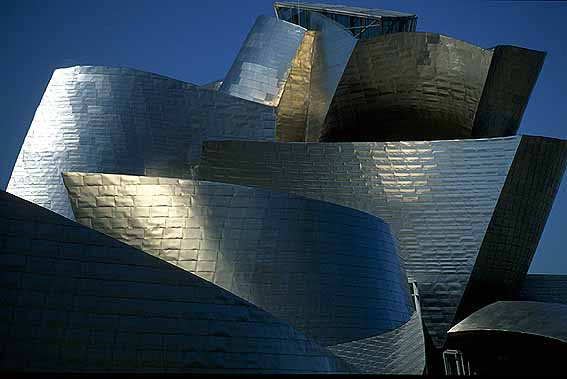

Then, in 1997, Gehry completed the titanium clad Bilbao Guggenheim. The museum has been described as the most important building of our time and it brought Gehry a great deal of fame.

‘Well they (the client) asked for the Sydney Opera House. They, they asked for that,’ Gehry told BBC Radio. ‘They said we want a building that does for Bilbao what the Sydney Opera House does for Australia, and I looked at him and I said okay. I didn't ever expect we'd achieve what we did, but it only was achieved because a certain amount of it is my talent, whatever, whatever you want to, however you want to judge that, but I had a incredible client and incredible City Government and, and people that were committed to doing something.’

Richard Lacayo, architecture critic at TIME Magazine, wrote, ‘But with the singular spectacle of his Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain - all that glistening titanium, those war-whooping arabesques - Frank Gehry in 1997 undid everyone's idea of what a building looks like. Ever since, his greatest influence has been this: he has profoundly reordered the idea of constructed space among people who don't think about buildings for a living but who work in them, live in them - and pay for them. Because of Gehry, the people who commission buildings are now happy to be offere d designs that sign the air in radically different ways.’

The Bilbao Guggenheim attracted more than a million visitors its first year, and suddenly Bilbao, a city that was previously unremarkable, became a tourist destination. The Guggenheim activated a renewed interest in architecture and the architecture's role in our society.

Moreover, its’ success galvanized Los Angeles into the long-awaited completion of the Walt Disney Concert Hall. Gehry had completed his design eight years earlier but the project had foundered amidst political infighting and funding shortages. Gehry’s design was blamed for being over cost and unbuildable and his commissions suffered as a result.

With the success of Bilbao, then LA Mayor, Richard Riordan, decided he wanted to build the LA concert hall after all. Gehry told BBC Radio:

‘He, I think he, he'd never seen anything like it and he heard about Bilbao and he heard what happened and he said we've got to build it. So he brought his, brought in his friend, and at that time my mortal enemy (billionaire investor) Eli Broad to run it, and Eli, God bless him, did it and, and we got through it and we're best friends now again, but it was dicey. What saved the whole thing in the end was Walt Disney's daughter, Diane Disney Miller … who stood by it and she, I didn't know her. I'd met her but I didn't know her, and she stood by it because she saw the attack on my work as being similar to what happened to her father in the early days when the studios used to beat him up, and she related it to that and she said I'm not going to let that happen’.

The Walt Disney

Concert Hall was completed in 2004 to an ecstatic public response. It has

become one of the great performance venues in the world, and not just for its

acoustics. It has transformed the skyline of downtown Los Angeles and become a symbol of culture.

The Walt Disney

Concert Hall was completed in 2004 to an ecstatic public response. It has

become one of the great performance venues in the world, and not just for its

acoustics. It has transformed the skyline of downtown Los Angeles and become a symbol of culture.

According to Richard Lacayo at TIME magazine, Gehry had shaken up the world of architecture, again. "[The Disney Hall] can be counted on to reverberate not just through L.A. but across the U.S., raising the stakes everywhere for what a building can be," he said.

Does Gehry ever get overawed by his own work?

‘If I get self conscious, I’m dead,’ he told the Sunday Times. ‘I just assume I’ll continue to push myself. I’m insecure. I never expect the building I’m doing to be great. So I try – and it is what it is. I’ve been lucky.’

Now in his 70s, Gehry refuses to slow down or compromise his vision. He and his team are working on a number of projects, including a spectacular Guggenheim museum in Abu Dhabi. A living legend, Frank O. Gehry continues to create his own language of architecture.