What separates 'Us' — the good guys — from 'Them', the baddies? Fundamentally, very little, says the founder of The Forgiveness Project, Marina Cantacuzino

What separates 'Us' — the good guys — from 'Them', the baddies? Fundamentally, very little, says the founder of The Forgiveness Project, Marina Cantacuzino

From the mass murderers of Auschwitz, to the Islamic extremists who flew their planes into the World Trade Center, the widespread belief is that those who do grave harm to others to fulfill their ideological purpose are fundamentally different from us. We use a special vocabulary for them: 'beasts', 'monsters', 'evil'. . .

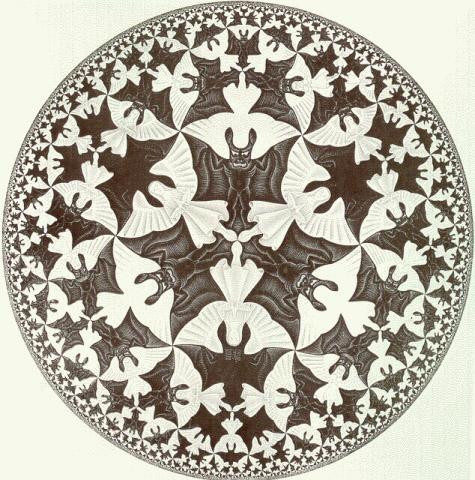

Yet the hypothesis which separates 'them' from 'us' does not serve to explain why such atrocities happen or how we might prevent them in the future. Revenge, resentment, and moral revulsion are a natural response to hurt, but they obscure analysis and perpetuate an age-old belief that good and evil are separate forces over which we have no control.

In The Gulag Archipelago (Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s account of the Soviet prison system under Stalin) the Russian writer and dissident gives an explanation for why we prefer not to take responsibility for humanity’s most heinous acts.

If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?

In similar vein, the author and Auschwitz survivor, Primo Levi, astonishingly remarked of his concentration camp guards:

These were not monsters. I didn’t see a single monster in my time in the camp. Instead I saw people like you and I who were acting in that way because there was Fascism, Nazism in Germany. Were some form of Fascism or Nazism to return, there would be people, like us, who would act in the same way, everywhere.

This idea is supported by Philip Zimbardo, the architect of the famous Stanford Prison Experiment. In his absorbing and masterly book The Lucifer Effect he explains how easily those in power can create a 'hostile imagination' through stereotyped conceptions of 'the other' as worthless, demonic, monstrous, and therefore a fundamental threat to our most cherished values and beliefs.

With public fear notched up and the enemy threat imminent, reasonable people act irrationally, independent people act in mindless conformity, and peaceful people act as warriors.

Zimbardo’s sobering verdict is that just about anyone could do just about anything.

The 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment, in which students were allotted roles as prisoners or guards in a mock prison, proved the point as in less than a week the ‘prisoners’ turned pathological and the ‘guards’ sadistic.

This was not the first study of its kind. An earlier experiment, just as ethically questionable and just as revealing, conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram, measured the willingness of study participants to obey an authority who instructed them to administer painful electric shocks on volunteers. Milgram concluded:

The extreme willingness of adults to go to almost any lengths on the command of an authority constitutes the chief finding of the study... Ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process.

Such experiments would not be allowed today, but they go a long way to explaining why US soldiers in Abu Ghraib became devoid of conscience and moral responsibility.

According to the late Alison Des Forges, a human rights activist and historian who tried to call the world’s attention to the looming genocide in Rwanda, such behaviour lies just under the surface of any of us. She once explained:

The simplified accounts of genocide allow distance between us and the perpetrators of genocide. They are so evil we couldn’t ever see ourselves doing the same thing.

Des Forges knew from her investigation into many atrocious crimes that minds can be so efficiently brainwashed that formerly peace-loving citizens can be persuaded to massacre their neighbours and support an ideology that purports punishing the powerful by murdering the innocent.

The simplified media accounts of genocide keep us distant from them but what would we do under terrible pressure if all our morals and values were threatened; if we believed our children to be in imminent danger? Once you start to reassert a murderer’s humanity — by trying to understand how and why they might have acted in such a barbarous way — then it becomes less easy to separate US from THEM.

It’s a very hard pill to swallow — to realise that probably most of us are capable of killing or at the very least hurting others if persuaded by those more powerful than ourselves.

Kemal Pervanic, a survivor of the notorious Omarska concentration camp in Bosnia, recently told me how, on returning to Bosnia some years later, he recognised the cruellest of his former camp guards standing by the road hitch-hiking; the sight caused Pervanic to start laughing. I asked him why. He explained:

What else could I do? I didn’t want to swear or scream or get violent. I laughed because I remembered the monster this man had been. But now, hitch-hiking alone on a dusty road, he looked almost pitiful. People describe these people as monsters, born with a genetically inherent mutant gene, but I don’t believe that. I believe every human being is capable of killing.

Follow Marina Cantacuzino on Twitter www.twitter.com/ForgivenessProj and at The Huffington Post.