I was so moved by new film The Sessions, written and directed by Ben Lewin, that I felt compelled to share its brilliance. Admittedly the story, about a severely disabled man, a virgin hiring a ‘sex surrogate’, did not appeal to me. In fact if I had not borrowed a BAFTA screener from my boss I would not have paid to see it at the cinema. And what a loss for me that would have been.

To be brutally honest, I had always found sex and disability in the same sentence icky. On top of that quiet prejudice, I ignorantly assumed a sex surrogate was just another fancy name for a prostitute.

The issue of ‘sexual surrogacy’ had come to my attention through a debate on Facebook months ago leaving me really none the wiser, and I had never considered the sexual needs of the disabled at all: in fact, I wrongly assumed, more likely than not, sex was out of the question for the majority of the physically disabled.

I remember in LA years ago when a girlfriend was dating a tall, dark and handsome man who had lost his entire right leg in a motorcycle accident. Rather than put women off, he was very much lusted after. Back then, age 25, I did not understand how that was possible. My own fear meant I could not see beyond his disability and compounded the prejudice lurking within me.

I should add that at that time I was using sex purely to back up my own diminishing identity, while developing an addiction to crystal meth, so I was hardly a shining light of wisdom and compassion, towards myself or others! But I do remember feeling shocked by my secret feelings towards this man and it was only while watching The Sessions, and afterwards mulling it all over, that I recalled my bad attitude.

The film is based on the real life of Mark O’Brian, an American polio survivor, beautifully played by John Hawkes, who lived to age 49 attached to an iron lung. He is so badly paralysed from age six that he spends his life lying down on a gurney where he is fed, washed, dressed and pushed around by various carers. He cannot do anything for himself so has lived a life of ‘unendurable crap’, although to his immense credit he has successfully graduated from University College Berkeley, California, and works as a poet and journalist by tapping at the keys with a stick controlled by his mouth. He also clearly has a fantastic, macabre sense of humour.

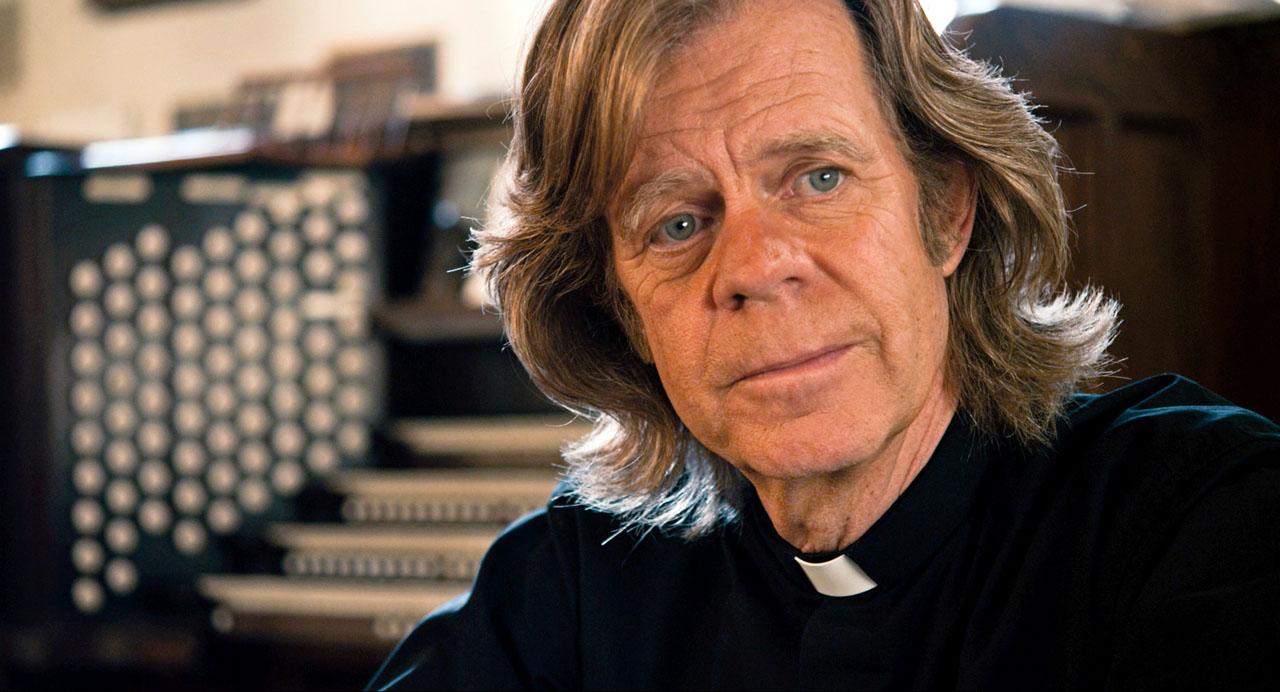

At the start of the film Mark, now in his mid 30s, has yet to experience physical and sexual intimacy, and the burden of being a grown-up virgin has become unbearable. He first confides his untenable position to his local Catholic priest — another brilliant turn from William H. Macy — who grants

Mark the ‘permission’ he craves, by responding from a human, rather than Catholic, point of view. This is where Cheryl Cohen-Greene, played by a luminous Helen Hunt, comes in.

The journey they go on together is so believable in the film that my misconceptions around sexual surrogacy are completely overturned. Cheryl’s job, like that of any kind of therapist, is to help her client make peace with their self in whichever area the client is lacking. In Mark’s case his disabled body, alongside a huge dose of Catholic guilt, physically and spiritually hold him back. Because Cheryl’s relationship with her own body and sexuality is admiringly straightforward and unfettered, she acts as a guide and teacher in human sexuality and body awareness. Her willingness to physically share herself with Mark is beautiful, and without her the last five years of Mark’s life, I suspect, would have been very different. I will not ruin the wonderful story for you by revealing the end, but it certainly validates the therapeautic value of sexual surrogacy.

In the film there is very little explanation of what the role of a sexual surrogate is, so I will add a few points made by UK sex surrogate Padma Veda. Through giving therapeutic lessons in sexuality, a surrogate is a ‘trained, supportive, temporary stand-in for the currently unavailable partner’. The ultimate goal is to help the client achieve sexual confidence alongside emotional intimacy. Sessions are no more than nine in total, and will cost at least £3000. Currently there are eight qualified practitioners in the UK but this is set to expand with Veda starting up training courses.

I learned an important message through the art of this feature film about our shared humanity: we all crave intimacy and it really is an invioable human right. It is also of immense value, staving off depression and promoting ‘feel-good’ hormones. Of course for some — due to mental and/or physical disability — it is much harder to achieve, but with people like Cheryl and Padma Veda to guide and educate, it is certainly possible if the individual is brave enough to take that first step.

Sometimes a film can be so powerful that it alters perceptions and opens up a whole new area of understanding around its subject that it makes it a joy to watch and a milestone in raising much-needed awareness around a misunderstood area. The Sessions is such a film so let’s hope it garners an Oscar, or two!