Almost every day in the news I read about another celebrity entering rehab, writes Clea Myers.

Almost every day in the news I read about another celebrity entering rehab, writes Clea Myers.

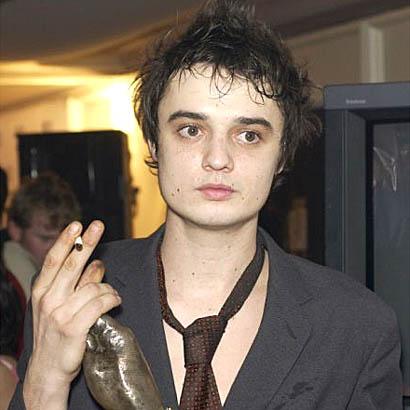

Or re-entering. Or leaving early. Pete Docherty, Amy Winehouse, Kerry Katona, Keith Urban, Britney Spears, Kirsten Dunst and Whitney Huston, to mention a few of the best known.

Often reporters highlight the superficial aspects of these treatment centres, as if they are describing a luxury spa. While there are disparities between levels of comfort within facilities, one unifying feature defines their existence: concentrated treatment for addictive illness.

Rehab is for sick people with a specific illness, just as hospitals treat a wide range. The location, interior décor, quality of food and extras provided, at a cost, are indicators of the breadth of the market. In truth, the core thrust of any self-respecting rehab will be the same.I write from experience of two trips to residential rehab within ten years.

The first time was in Los Angeles in 1996. I was addicted to a little-known substance called crystal meth that had seen me lose the plot quite spectacularly. Having crashed my car, I decided to wash cheques and cash them in Beverly Hills banks, dressed up to the nines and wearing a wig. On the side, I was planning a burglary that I ditched in favour of a quiet night in at my dingy studio apartment in the heart of seedy Hollywood.

Following my first arrest I panicked and realised it never would have happened had I not been off my head on drugs. I had lost any sense of reality due to the drug itself, combined with four-day stints awake and minimal nutrition.

I was in a highly fragile state and having contacted my family for help, followed their lead and checked into Promises in West Los Angeles (it has since upgraded and re-located to Malibu). I had no money or work and a court hearing to attend. Rehab was clearly the best place for me.

It was a serious wake up call.

I come from a family that has been blighted with addiction for at least three generations, in its most obvious form of alcoholism. Because no one ever admitted there was a problem, denial set in and the subject was never broached. I was conscious of my mother’s shame and this I believe kept her silent, whereas my father relied on my schooling for that kind of guidance.

My rehab initiation period - the first two to three weeks of a five-week stay - entailed attacks from all angles on my deep-seated denial.

I should mention that all addicts are ‘in denial’ as part of the psycho-pathology of the illness - the illness tells the sufferer that they do not have it. Therefore many sessions - one-to-ones and group therapy - use the mirroring technique, whereby patients and counsellors alike (most counsellors are recovering addicts themselves) point out and flag up delusional thinking patterns, excuses and justifications.

A boulder that blighted my acceptance of the ‘disease’ concept was the idea that to recover I needed to abstain from all mood-altering substances, including alcohol. I readily agreed that crystal meth was the devil-incarnate and should never be used again, but what of a glass of red, even a couple, alongside a steak?

A process started whereby I re-examined what my relationships with addictive substances were. In truth, more often than not, I drank more than I intended, losing control. I had smoked since I was 13. I binged on chocolate when I felt low. Cocaine had offered temporary release from depression and ultimately crystal meth had subsumed all my negative feelings into oblivion, replacing them with a super-charged buzz that drove me mad, within months.

Facing my own evidence of addictive behaviour precipitated a pink cloud period. I was bursting with joy and anticipation of my new life, clean and serene. I knew what the problem was and I had been given a solution: free membership to Narcotics Anonymous, with a tailored program to work.

If only . . .

Within four months I returned to using crystal meth, believing this time I could control it, having learned all sorts of tricks-of-the-trade from more seasoned rehab attendees. I failed miserably and within eight months was unofficially deported from LA to the UK.

Back in London I was arrested and sectioned; I was suffering with drug psychosis. Now my recovery was essential because my addiction was placing my life in serious danger.

Unfortunately, there was no money to pay for my treatment and the help I received on the NHS was wholly inadequate. Rather than use the tools I had been given at Promises back in LA, I chose not to go to a 12-step fellowship, like Narcotics Anonymous, for help.

I had made a sick kind of bargain with myself: give up drugs, but drinking is OK.

Undoubtedly, I craved the emotional blunting that alcohol gave me. Having almost accomplished my self-destruct mission while in LA, my deep-seated shame and guilt justified the occasional release that alcohol afforded me. After all, alcohol is legal and, in the UK, highly acceptable. In fact, in my experience being teetotal is viewed with disdain, especially when I was an aspiring thespian back in the late 1990s.

Ten years later and I went into rehab - Promis in Kent - for the second time. I had long given up drugs, or at least used them on a very occasional basis, but had developed a serious problem with alcohol. I was a binge drinker who got drunk between one to three evenings a week. I could stop for a few months at a time, but invariably would return to the same pattern of use.

I was also experiencing an early menopause at the age of 36 and this coupled with my bingeing brought me to my knees. I was exhausted physically and emotionally. I could stop drinking for around four months and then I would relapse. The relapses were soul-destroying because of the recurrent theme of self-sabotage.

I was very grateful to check-in to Promis. I had an entire month to focus entirely on myself and my emotional needs. What an incredible gift!

By the time I arrived I was bursting with unexpressed emotion - predominantly anger - and I was a challenging patient for some of my stay. But that time away - for recuperation, support, understanding, therapy and learning - enabled me to grapple with the reality that recovery from addiction is a life-long process.

My first time in rehab, back in 1996, was the introduction, and now I am entirely ready to accept I am an addict who has an illness that knows only destruction if left untreated. This was my journey; other addicts might understand their predicament more quickly than I was capable of.

I still grapple with the 12-step philosophy- I am highly analytical by nature - and I abhor ‘program-speak’. However, a worldwide support network is in existence if I choose to use it. And attendance at meetings has become an antidote to the isolation I often feel as a recovering addict, as well as countering denial. I have a wonderful sponsor, who is also a Buddhist and it was she who suggested I take my Gohonzon (Buddhist scroll) into rehab with me. I had it by my bed, on the widow-sill, and I chanted morning and evening.

As a Buddhist I found it very hard to admit complete and utter powerlessness over my addictive illness, but I have ultimately surrendered to this concept. I fought it for years and my illness re-surfaced as alcoholism. Basically my illness stayed with me, regardless of whatever chemical I favoured. And in the case of my addiction I believe I had to surrender to win. This is just one of the many paradoxes I have come across in recovery.

My hope is that society will accept addictive illness as that: an illness that can be treated through abstinence and a day-by-day recovery program. Historically similar attitudes existed towards epilepsy, diabetes and other mental disorders like bi-polar and schizophrenia. I had to alter my own perceptions and understanding in order to make the correct adjustments in my own life.

Today I am grateful and happy that I was given another chance to re-assess my position and try rehab again - for the second and last time.