Welcome to the ezine produced by SGI Buddhists that prompts the positive, kindles the constructive, highlights the hopeful and leaves you feeling - well, up!

Money. A popular subject. And more so now than ever, when so much of it seems to have mysteriously disappeared. Eddy Canfor-Dumas investigates from a Buddhist angle

In 2008 the world experienced the greatest financial crisis since the Wall Street Crash of 1929, and in this country we’re currently inching out of the worst recession for more than sixty years. We have a record public debt and no one quite knows how paying it off is going to affect their taxes, their jobs or the services on which they might rely, now or in the future. A lot of people are worried. Some are scared. Nearly everyone is concerned, even if the effects haven’t yet reached them.

Most people think about money in a pretty straightforward way: How can I get some? How can I keep it? How should I spend it? And how can I get some more? But I'd like to encourage you to delve deeper. Because I think Buddhism has some very interesting things to say about money, and which touch directly on the current state of the world’s finances.

I’ll start with some comments on the recent crash by Daisaku Ikeda, the president of Soka Gakkai International (SGI), the international Buddhist lay organisation to which I and others involved with This Way Up belong. The comments come from his 2009 Peace Proposal – he publishes one each year on 26 January, and this year was his twenty-eighth. He says:

When looking at the present financial crisis, we have to ask if we as a society have not … fallen prey to the Medusa-like spell of the abstract and anonymous world of currency, losing our essential human capacity to see through to the underlying fact that – however necessary it may be to the functioning of human society – currency is nothing other than an agreement, a kind of virtual reality.

If, for example, a company loses sight of its public aspect of contributing to the larger society, and serves only the private interests of its stockholders – their insistence on short-term profit – it will relegate to secondary or even tertiary importance its concrete connections with the real world of real people, whether these be management, employees, customers or consumers.

…The time has now come for a new way of thinking, for a paradigm shift that will reach to the very foundation of human civilization.

So I hope this article will offer a new way of thinking, based on Buddhist teachings, that could help us make the paradigm shift that Daisaku Ikeda urges in the passage above.

In doing this I’m aware, of course, that religion and money have never made comfortable bedfellows. In fact most people think of them as being diametrically opposed. ‘The love of money is the root of all evil,’ warns Timothy in the Bible, with Matthew adding that, ‘It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God’. The painting on the left of Christ driving the money-lenders from the temple, attributed to the 17th century French painter Le Valentin, is typical of the traditional Christian attitude.

The tension between the spiritual and the material side of life can be seen in Buddhist teachings, too. Shakyamuni, the historical founder of Buddhism, felt he had to renounce his life of luxury as a crown prince if he was to find the answer to what he saw as the four inescapable sufferings of human life: birth (into this world of anguish), ageing, sickness and death. And in many parts of the world, notably the countries of Southeast Asia, his example is still followed today by Buddhist monks. They, too, have largely renounced the material world – by tradition they are allowed to own just three robes, a girdle, an alms-bowl, a razor, a needle and a water strainer; and they live by begging food each day from lay believers.

One reason why people tend to think of religion and money as incompatible is that when they mix the result is so often flagrant corruption. And it seems that the basic pattern is the same for all ages and all religions. From the sale of indulgences by the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages to some modern day American TV evangelists, the unscrupulous religious practitioner convinces a gullible congregation that they can gain spiritual or material benefit, in this world or the next, through financial donation. And then he or she uses the money to fund a lavish lifestyle.

Buddhism has not been immune to this corruption. So wealthy did some monasteries grow in Japan between the 10th and 16th centuries, for example, that they formed private militias of armed Buddhist monks – the sohei – to defend their property, attack rival sects and even threaten the government.

In fact, Shakyamuni taught that spiritual decline is inevitable in any successful religion, including Buddhism.

Initially, a religion’s growth is fuelled by the purity of its pioneers, men and women who clearly recognise its benefits and share it enthusiastically with their friends and families. But as the religion gradually becomes established in society, as the congregation grows and the money pours in and magnificent buildings are erected, little by little it loses its original purity of purpose. A priestly class grows up that increasingly becomes more intent on protecting the material wealth it has accumulated than the spiritual well-being of its followers; and so inevitably a divide grows and widens between clergy and laity. Eventually, says Shakyamuni, the religion falls into conflict with itself – ‘reformists’ clash with ‘conservatives’; ‘fundamentalists’ with ‘progressives’; ‘idealists’ with ‘realists’. And the conflict is as much about material style as spiritual doctrine.

I’m sure, as I describe this, some of you will be thinking of the history of the Christian Church; for example, of how the excesses of the Medici pope Leo X helped trigger the Reformation. But an equally decisive split occurred in Buddhism in the centuries that followed Shakyamuni’s death.

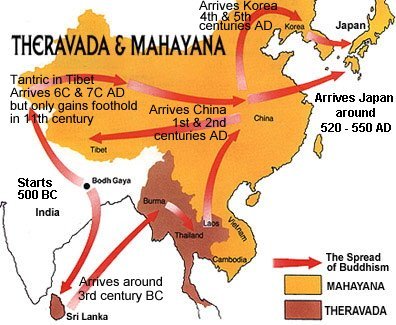

Broadly speaking, this split also centred on the relationship of the material to the spiritual. But while the Reformation arose as a reaction to the material corruption of the Catholic Church, the Buddhist Mahayana movement grew from the opposite pole – as a reaction to the extreme spiritual conservatism of monastic Buddhism.

Mahayana Buddhists objected to the view that one could become enlightened only by renouncing ordinary daily life, entering a monastery and devoting oneself entirely to spiritual practice. This was not what the Buddha had intended, they argued – he had preached a path to enlightenment for all, not merely an elite few. And besides, these monks were only able to devote themselves to their spiritual path thanks to the material support of the lay community, who could benefit only indirectly.

Mahayana means ‘Greater Vehicle’ and indicates the desire of this movement to promote a teaching that could carry all people to enlightenment; monastic Buddhism they labelled Hinayana, the ‘Lesser Vehicle’, that could carry only a few to the same goal (though this negative term is now generally avoided, Theravada – ‘school of the elders’ – being preferred).

Not surprisingly, Mahayana Buddhism attempts to reconcile the material and spiritual aspects of life. For example, the Vimalakirti Sutra relates how Shakyamuni hears that one of his lay followers, the wealthy citizen Vimalakirti, has fallen ill, and how he asks ten of his major disciples to visit and encourage him. But each disciple in turn declines, explaining that Vimalakirti has at one time or another bested him in understanding the Buddha’s doctrines. Eventually, one disciple visits the sick man and asks what is wrong with him. ‘Because the beings are ill, the bodhisattva is ill,’ Vimalakirti replies, adding, ‘The sickness of the bodhisattva arises from his great compassion.’ He is demonstrating that the ideal Mahayana bodhisattva makes no distinction between himself and others, and takes on their suffering so that both he and they will be able to attain enlightenment together.

But significantly, Vimalakirti is not only wise and compassionate – he is also filthy, stinking rich! (Interesting how these adjectives have become attached to the word ‘rich’ – evidence of the view, perhaps, that too much wealth is inevitably corrupting.)

Moreover, Vimalakirti is also a lay believer. In other words, Mahayana Buddhism sees no fundamental contradiction between spiritual and material wealth, and a rich man may be equally – even more – enlightened than the Buddha’s closest priest-disciples. No camels and eyes of needles here.

In fact, recent scholarship by the American academic Gregory Schopen entirely debunks the image of the Buddha as a world-renouncing sage. He argues that, as the leader of a community of followers, he was more likely to have been a combination of astute businessman, economist and lawyer – in other words, acutely aware of the ways of the world, but spiritually disciplined enough not to be corrupted by them.