Everything has its essential point, and the heart of the Lotus Sutra is its title… Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. Truly, if you chant this in the morning and the evening, you are correctly reading the entire Lotus Sutra (Writings of Nichiren Daishonin vol 1, p. 923).

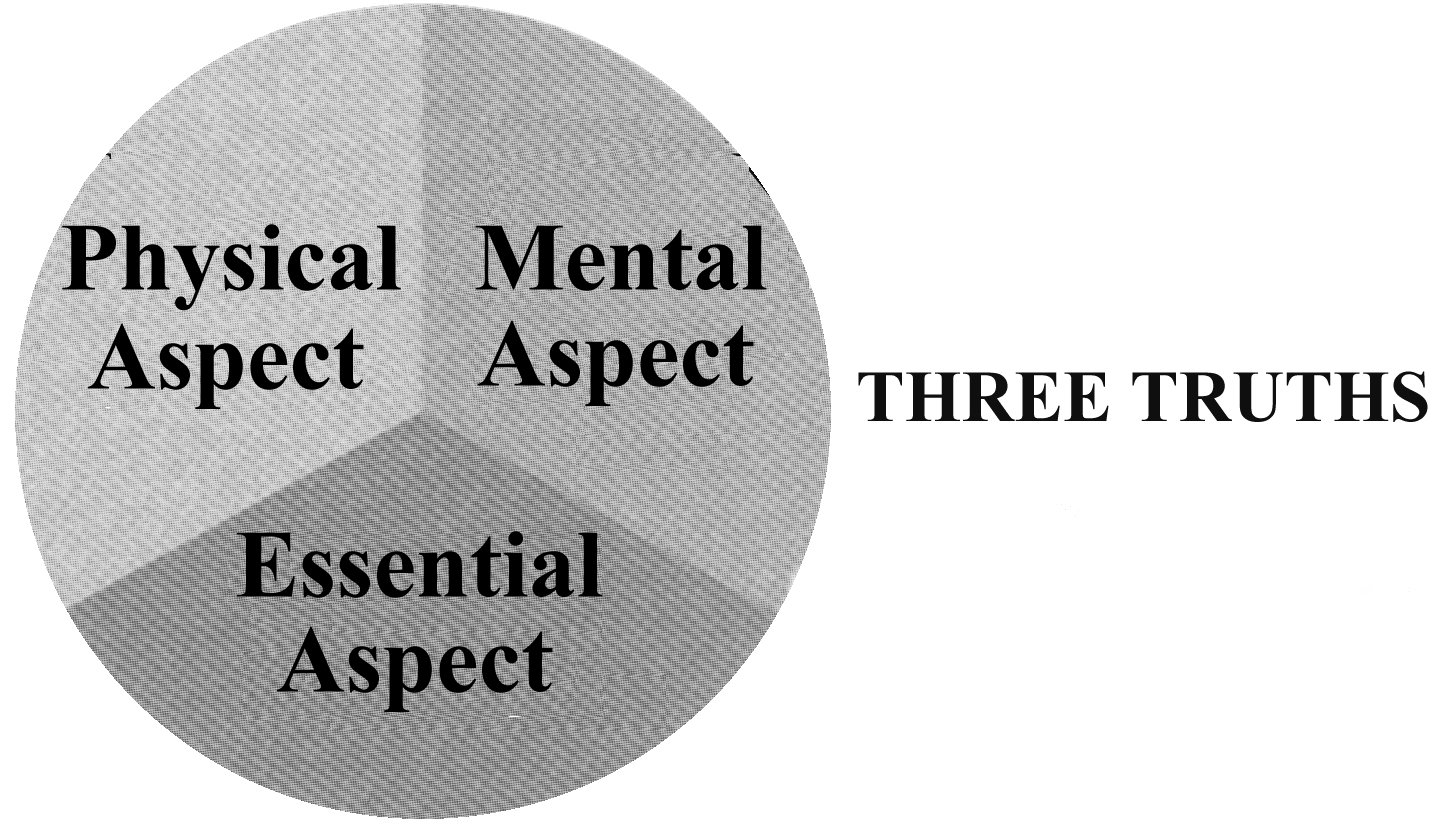

According to Nichiren, Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is not simply the essence of the Lotus Sutra, it is the true entity or essence of all things. In other words, in terms of the Three Truths, it corresponds to the essential aspect. And so chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo gives us a concrete means to turn the theory of the Three Truths into practical reality. Richard Causton explains:

Going back for a moment to the analogy of the two horses pulling the wagon, Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is equivalent to the driver, the Middle Way, and chanting therefore gives us the strength and wisdom to keep the horses of [the physical and the spiritual aspects of] our lives pulling together in the right direction.

I can give an example of this. Some years ago I was sent a book by a film producer and asked if I’d like to adapt it into a film. I’d long wanted to write a feature film, and here was the chance. Plus I needed the money – as ever. Moreover, this book, a spooky crime thriller, was a bestseller by a big name author, so the script I wrote had a good chance of actually reaching the screen – an important factor for a screenwriter in deciding what projects to take on.

I sat down to read – and was hooked. It was a gripping story, well told, and I read the second half in a single three-hour session – in the bath! But – when I got to the end I felt empty and slightly disgusted, for not only did the novel deal in graphic detail with necrophilia and extreme sadistic sex, somehow I felt it wasn’t actually about anything. It had no heart.

So I chanted about it and very quickly realised that I didn’t want to help bring this story to an even wider audience, even if I would personally benefit. So I turned it down, with no regrets, along with the substantial sum I would have been paid to write it.

In other words, despite the material temptations the job held (the physical aspect) and the chance to fulfil a personal ambition (the non-physical, mental aspect) by basing my decision on Nam-myoho-renge-kyo (the essential aspect) I feel I was able to do the right thing; for my life, anyway. And, as often happens in practising this Buddhism, another job came along soon afterwards that I was able to accept with genuine enthusiasm.

But chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo isn’t just a means of holding the reins between the spiritual and material aspects of one’s life. It works on a much more profound level to sustain and develop one’s life as a whole. Nichiren teaches that by chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo we cultivate our life at its essence and see the fruits in the form of both spiritual and material benefits. The spiritual benefits might be summed up as developing the qualities of the Buddha, particularly our own wisdom, courage and compassion. While the material benefits might be seen in improved health, better relationships with other people and – yes – greater wealth.

At this point it’s important to emphasise that the fundamental aim of this practice is not to become materially rich. In a letter to one of his followers, for example, Nichiren says:

More valuable than treasures in a storehouse are the treasures of the body, and the treasures of the heart are the most valuable of all. From the time you read this letter on, strive to accumulate the treasures of the heart! (WND-1, p. 851)

The treasures in a storehouse are material wealth; the treasures of the body are good health and our physical qualities and talents. Neither treasure is unimportant, but of supreme importance are the treasures of the heart – the wisdom, courage and compassion for others that I just mentioned. Far from being a means to get rich quick, Nichiren’s Buddhism places the utmost emphasis on learning the supreme value of human life itself. In another letter he says: 'Life is the most precious of all treasures. Even one extra day of life is worth more than ten million coins of gold' (WND-1, p. 955). And in yet another he says:

Life is the foremost of all treasures. It is expounded that even the treasures of the entire major world system cannot equal the value of one’s body and life. Even the treasures that fill the major world system are no substitute for life (WND-1, p. 1125).

This is very clear. It is not the material side of life that Nichiren’s Buddhism emphasises; that is important, but much less important than one’s basic humanity.

Some years ago, however, some parts of the media got the idea that this practice is simply about chanting for material wealth, for Porches and big houses and fabulous jobs, and labelled members of SGI-UK ‘designer Buddhists’. So how did this come about?

Some years ago, however, some parts of the media got the idea that this practice is simply about chanting for material wealth, for Porches and big houses and fabulous jobs, and labelled members of SGI-UK ‘designer Buddhists’. So how did this come about?

Well, it is undeniable that members are encouraged to chant to fulfil their desires, whatever they are. This is because to practise this Buddhism is to embark on a process of change, dubbed ‘human revolution’. It takes people as they are, now, and encourages them to chant for whatever is in their hearts at this moment, in the confident expectation that the chanting itself will cultivate the essential aspect of their lives and so gradually deepen and broaden their outlook. Many people in contemporary society have strong material desires – so this is what they chant about. But in the process of chanting they develop the spiritual side of their lives. If they were told they couldn’t chant for more money or a bigger house or a better job, they might not start chanting at all.

Human revolution can work the other way, too. For example, when I started to chant I was, if anything, too careless about money. I lived from hand-to-mouth, with a lazy attitude, easy-come-easy-go. Except it wasn’t especially easy come, just easy go. As a consequence I was often broke. Money was not what prompted me to start chanting, but over my years of practice chanting prompted me to ‘get real’; to take money seriously, and treat it seriously, with respect – but without making it the dominant factor in my life. As a result, I now have a lot more of it.

This brings me to another fundamental point. Buddhism teaches that the good fortune or lack of it that we experience in this world is the result of our karma – the effects we receive from the causes we make. This karma is not made in this lifetime alone. Buddhism explains that life is eternal, and that if the causes we make in one lifetime do not bear fruit before we die, they will inevitably produce effects in a future lifetime. Nichiren elaborates on this point:

One who climbs a high mountain must eventually descend. One who slights another will in turn be despised. One who deprecates those of handsome appearance will be born ugly. One who robs another of food and clothing is sure to fall into the world of hungry spirits. One who mocks a person who observes the precepts will be born to an impoverished and lowly family. One who slanders a family that embraces the correct teaching will be born to a family that holds erroneous views. One who laughs at those who cherish the precepts faithfully will be born a commoner and meet with persecution from one’s sovereign. This is the general law of cause and effect (WND-1, 305).

However, while it is our karma that determines the circumstances into which we are born in this world, and the good fortune – or lack of it – that we experience, the story does not end there. The key question is what do we do now, in the face of this karma? Essentially, Nichiren teaches that our karma is not so much a matter of what we may have done in the past, but what our fundamental attitude to life is in the present.

However, while it is our karma that determines the circumstances into which we are born in this world, and the good fortune – or lack of it – that we experience, the story does not end there. The key question is what do we do now, in the face of this karma? Essentially, Nichiren teaches that our karma is not so much a matter of what we may have done in the past, but what our fundamental attitude to life is in the present.

For example, a person may be born into a wealthy family but be foolish and feckless. It is highly likely, then, that he will simply squander his material good fortune. On the other hand, a person may be born into a poor family but be shrewd, hard-working and determined. As a consequence, it is highly likely that she will be able to accumulate material good fortune. The world is full of both examples.

To change our karma, then, Nichiren teaches that we have to change our fundamental attitude to life, an attitude that is so deeply ingrained that we may not even be consciously aware that we hold it. The way we look at the world, the way we react to it, might seem so obvious and natural, so much a part of ourselves, that we may never question it. We can, however, when we start to chant.

Buddhism teaches that our fundamental attitude arises from one of what it labels the Ten Worlds, or ten basic conditions of being.

Hell

the world of suffering

Hunger

the world of insatiable desire

Animality

the world where instinct dominates reason: as a result, our foolishness often rules

Anger

the world of the ego, where we clash with others

Humanity

the world of calm, where our reason dominates

Rapture

the world of pleasure that we experience when our desires are satisfied

Learning

the world where we are eager to learn from others

Realisation

the world where we work things out for ourselves

Bodhisattva

the world where we care for others

Buddhahood

the world of joy, where we feel complete satisfaction in our struggle to create value for ourselves and other people

Buddhism explains that we all have all of these ten worlds, these ten basic states of life, and that each 'contains' all the others. For example, we may be in rapture at one moment – when a large cheque unexpectedly drops on the doormat; only to be plunged into hell at the next – when the next letter turns out to be a large demand from the Inland Revenue. In other words, the world of rapture 'contains' the world of hell, which can be revealed given the right cause. Similarly, if we open the tax demand first and then the large cheque, we might move from the world of hell into the world of rapture, as we realise with relief that we unexpectedly have the money to meet the demand; this shows that the world of hell likewise 'contains' the world of rapture.

But while we each possess all of the ten worlds, one is normally dominant; this is our ‘default’ life condition, the one to which we usually gravitate and in which we spend most time. An academic, for example, might be dominated by the world of learning or realisation; a nurse might be dominated by the world of bodhisattva. But whichever world it is, the key thing to understand is that our dominant life condition colours our thoughts, feelings, words and actions, and so shapes the reality in which we live in the present and future. So Buddhism would say that it is the worlds of learning and realisation within her that led the academic to become an academic, and the world of bodhisattva within him that led the nurse to become a nurse.

Now, the key point is that the ten worlds shape our basic attitude towards money, too, and so influence our financial karma, the good fortune or misfortune we possess in this area. And this is what many people are particularly interested in.

Some years ago, however, some parts of the media got the idea that this practice is simply about chanting for material wealth, for Porches and big houses and fabulous jobs, and labelled members of SGI-UK ‘designer Buddhists’. So how did this come about?

Some years ago, however, some parts of the media got the idea that this practice is simply about chanting for material wealth, for Porches and big houses and fabulous jobs, and labelled members of SGI-UK ‘designer Buddhists’. So how did this come about? However, while it is our karma that determines the circumstances into which we are born in this world, and the good fortune – or lack of it – that we experience, the story does not end there. The key question is what do we do now, in the face of this karma? Essentially, Nichiren teaches that our karma is not so much a matter of what we may have done in the past, but what our fundamental attitude to life is in the present.

However, while it is our karma that determines the circumstances into which we are born in this world, and the good fortune – or lack of it – that we experience, the story does not end there. The key question is what do we do now, in the face of this karma? Essentially, Nichiren teaches that our karma is not so much a matter of what we may have done in the past, but what our fundamental attitude to life is in the present.