Welcome to the ezine produced by SGI Buddhists that prompts the positive, kindles the constructive, highlights the hopeful and leaves you feeling - well, up!

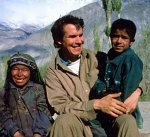

Greg Mortenson's passions are mountain-climbing and running marathons. But since 1993 he has dedicated his life to building schools and promoting community-based literacy programs in remote regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Greg Mortenson's passions are mountain-climbing and running marathons. But since 1993 he has dedicated his life to building schools and promoting community-based literacy programs in remote regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

By Vida Adamoli

Greg Mortenson’s love of mountains was sparked in childhood. He first climbed Mount Kilimanjaro while living with his missionary parents in northern Tanzania. Later, as trauma nurse in Los Angeles, he continued to dedicate most of his time to his twin passions of climbing and running. This changed in 1993 when, following the death of his epileptic sister, Christa, he joined an expedition to K2 as medic.

On this occasion climbing the world’s second highest mountain was more than a sporting challenge. It was his way of honouring Christa’s memory. During the climb one of the party developed severe altitude sickness. In a dramatic rescue, Mortenson and three other climbers fought to bring him back down to safety. By then they been on K2 for seventy days and were weak and exhausted.

Furthermore Mortenson was also suffering the effects of spending too long at ultra-high altitudes. This resulted in him becoming disorientated, separating from the others and getting lost.

Eventually, filthy and bearded, he staggered into the remote Balti village of Korphe. One of the inhabitants took Mortenson to his smoky hovel and nursed him back to health. The full extent of Korphe’s abject poverty only hit Mortenson when he was able to walk around. It was then he realized what sacrifices his host had made to feed him and put sugar in his tea. He also saw children having a rare lesson with a visiting teacher. They were squatting on the ground writing with a stick in the dirt. There was no school in Korphe and never had been. At that moment Mortenson vowed to repay his debt of gratitude by building the village a school.

He returned to America and immediately set about raising the necessary $12,000. To save money he moved out of his comfortable flat and lived in his car. He sent 380 letters to celebrities asking for a financial contribution. His one reply was from an NBC newsreader, who kindly donated $100.

At this point Mortenson sold his climbing gear, his car and camped out on a friend’s sofa.

But eventually his luck began to change. Learning that one cent would buy a Pakistani child a pencil, children at a school in Wisconsin collected 62,345 cents. Then a friend wrote a piece about Mortenson’s project for the American Himalayan Foundation newsletter. It was read by Dr Jean Hoerni, a Silicon Valley pioneer and climber, who promptly sent him a cheque for the entire $12,000. The accompanying note said, ‘Don’t screw up.’

Mortenson made the long trip back to Korphe. The villagers were stunned to see him. They never expected him to keep his promise to return.

There were many setbacks and challenges before the school was finally completed. To start with a bridge had to be constructed across a wide gorge, so that building materials could reach the site. As this hadn’t been calculated, Mortenson was obliged to return to America to seek more funds.

Eventually the five-room building became the template for the others that followed.

In 1996, together with Dr Hoerni, Mortenson founded the Central Asia Institute (CAI), an organization providing skilled labour, as well as materials such as stone and steel girders. In an article in The Daily Telegraph, Jonathon Foreman quotes Mortenson: ‘The village has to come up with the land, wood, sand and subsidised manual labour. Each house gives a certain number of days. We try to get them to match what we are giving. It’s not about money, it’s about getting the village to invest in the school.’

In the same article Foreman explains that Mortenson’s local staff are ordinary people, rarely educated past their early teens. What motivates them is their dedication to the cause of literacy. Sarfraz Khan (a former smuggler who travels on horseback equipped with a laptop and satellite phone), recalls his first meeting with the man they call ‘Dr Greg’. ‘I see a very helpful man. He is not saying, “I am big, I am American.” He goes to every poor home and sits with the people. In Pakistan, rich people have a different style. They don’t listen to poor people. Dr Greg is different, so the people like him.’

The work is fraught with danger. In 1996 Mortenson was held for eight days by armed kidnappers in Pakistan's Northwest Frontier Province. In 2003 he escaped a firefight between Afghan opium warlords. He has been served a fatwa by an angry Islamic cleric for educating girls and he receives hate mail and death threats from anti-Muslim Americans. But his commitment to promoting education and literacy in remote mountain regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan is absolute. It is his mission and nothing will stop him.

On the subject of educating girls, Mortenson says, ‘…it is the most important investment all countries can make to create stability, bring socio-economic reform, decrease infant mortality, decrease the population explosion, and improve health, hygiene, and sanitation standards globally.’ Recently it was reported by BBC that his efforts have resulted in over 25,000 children being educated.

Greg Mortenson’s book, Three Cups of Tea, is published by Penguin.