Welcome to the ezine produced by SGI Buddhists that prompts the positive, kindles the constructive, highlights the hopeful and leaves you feeling - well, up!

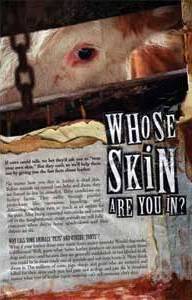

Despite the growing concern about the way we raise our farm animals, many of us don’t think twice about wearing leather writes Julia Stephenson.

Despite the growing concern about the way we raise our farm animals, many of us don’t think twice about wearing leather writes Julia Stephenson.

This may be because of the general assumption that leather is a by-product of the meat industry, but this is increasingly not so. As Tara Garnett of the Food Climate Research Network explains, "global production of raw cattle hides grew 24% between 1984 and 2004 - a faster growth than the production of cattle meat, at 19% over the same period.

Conventional leather production rivals the cotton industry in toxicity. A vast array of acids, salts, fungicides and bactericides - as well as chromium, sulphides and sulphates are used to process the hides. The result is a huge amount of water wastage, chromium sludge, and solid and airborne chemical waste. The bulk of leather processing has been outsourced to developing countries, where, according to critics, it's difficult to monitor standards.

A PETA investigation into cattle slaughter in India — where many people mistakenly believe that cows are treated well because they are revered by some Indians — revealed that old cows are sold at auction and then marched long distances to illegal transport trucks. Often sick and injured from the gruelling march, as many as 50 cattle are crammed into trucks designed to hold no more than a dozen animals. They are then driven over rutted roads—all the while goring and trampling each other—to ancient slaughterhouses where all four feet are bound together and their throats are slit.

Equally disturbing is the popularity of goods and clothes made from 'exotic' skins.

I shudder in revulsion when I pass shops stuffed full of bags and shoes made from creatures that have lived and died in appalling conditions.

It seems astonishing that anyone can gain pleasure from owning products made from the skin of snakes and lizards which have been skinned alive because of the belief that live flaying makes leather suppler.

Other `exotic’ animals, such as alligators, are factory-farmed for their skins and meat. Young alligators are often kept in tanks above ground, while bigger animals live in pools half-sunken into concrete slabs. According to Florida’s regulations, as many as 350 6-foot alligators can legally inhabit a space the size of a typical family home. One Georgia farmer had 10,000 alligators living in four buildings, where “hundreds and hundreds of alligators fill every inch of each room,” according to the Los Angeles Times. Although alligators may naturally live up to 60 years, farmed alligators are usually butchered before the age of 2, as soon as they reach 4 to 6 feet in length. Humane treatment is not a priority for those who poach and hunt animals to obtain their skin or those who transform skin into leather. Alligators on farms may be beaten to death with hammers and axes, sometimes remaining conscious and in agony for up to two hours after they are skinned.

Other `exotic’ animals, such as alligators, are factory-farmed for their skins and meat. Young alligators are often kept in tanks above ground, while bigger animals live in pools half-sunken into concrete slabs. According to Florida’s regulations, as many as 350 6-foot alligators can legally inhabit a space the size of a typical family home. One Georgia farmer had 10,000 alligators living in four buildings, where “hundreds and hundreds of alligators fill every inch of each room,” according to the Los Angeles Times. Although alligators may naturally live up to 60 years, farmed alligators are usually butchered before the age of 2, as soon as they reach 4 to 6 feet in length. Humane treatment is not a priority for those who poach and hunt animals to obtain their skin or those who transform skin into leather. Alligators on farms may be beaten to death with hammers and axes, sometimes remaining conscious and in agony for up to two hours after they are skinned.

Kid goats may be boiled alive to make gloves and the skins of unborn calves and lambs—some purposely aborted others from slaughtered pregnant cows and ewes—are considered especially “luxurious.”

Shearling, contrary to many consumers’ misconceptions, is not sheared wool; the term refers to a yearling sheep which has been shorn once. A shearling garment is made from the skin of a sheep or lamb shorn shortly before slaughter; the skin is tanned with the wool still on it.

Meanwhile hundreds of thousands of dog and cat skins are traded in Europe each year (with an estimated 2 million dogs and cats killed in China to meet the demand). Many are bought by unsuspecting consumers because the products made from dog and cat fur are often deliberately mislabelled and do not accurately indicate their origin. In France, more than 20,000 cats are stolen for the skin trade annually. During a police raid on a tannery in Deux-Sèvres, France, 1,500 skins, used to make baby shoes, were seized. When you buy leather products, you may unknowingly be purchasing leather from dog and cat tanneries.

Fortunately there is a lot we can do as consumers to stop this barbarity.

There are many alternatives to leather, including cotton, linen, rubber, ramie, canvas, and synthetics. Chlorenol (called “Hydrolite” by Avia and “Durabuck” by Nike) is an exciting new material that is perforated for breathability and is used in athletic and hiking shoes. It stretches around the foot with the same “give” as leather, gives good support, and is machine-washable.

And think twice about buying small leather goods. Every year I used to buy a leather diary, but this year I realized it didn’t matter if it was leather or leather substitute, so I opted for the latter. Similarly, I don’t care if my watch straps and bags are leather or not. The same goes for many other small goods, like key rings.

2 million pairs of leather shoes a year are currently dumped in UK landfill. We can make sure we look after our existing shoes so well that we don’t need to replace them as often. And when we do, we can really walk the walk by choosing footwear made from an alternative, even more attractive, material.

For vegans, there are composite shoes with recycled rubber soles, and Beyond SkinTerra Plana, have combined this with other reclaimed fabrics. Meanwhile top end designers, like Stella McCartney, who eschew cruelty yet still manage to produce lovely clothes, (pictured) are doing their bit to bring compassion to fashion. also uses no animal products. To ameliorate the problem of using animal skins, there is also E-leather, a British-made material using the bovine leather scraps usually dumped in landfill. Some shoe manufacturers, like

For vegans, there are composite shoes with recycled rubber soles, and Beyond SkinTerra Plana, have combined this with other reclaimed fabrics. Meanwhile top end designers, like Stella McCartney, who eschew cruelty yet still manage to produce lovely clothes, (pictured) are doing their bit to bring compassion to fashion. also uses no animal products. To ameliorate the problem of using animal skins, there is also E-leather, a British-made material using the bovine leather scraps usually dumped in landfill. Some shoe manufacturers, like