Welcome to the ezine produced by SGI Buddhists that prompts the positive, kindles the constructive, highlights the hopeful and leaves you feeling - well, up!

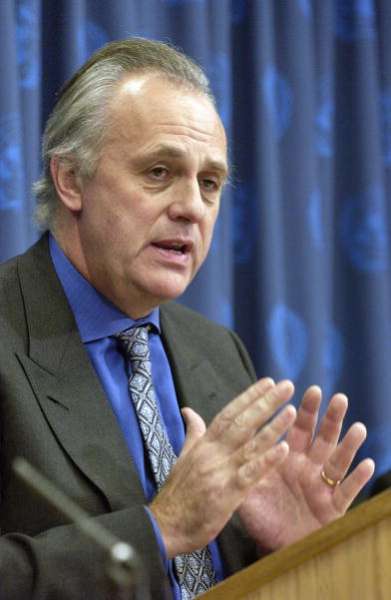

Formerly No 2 at the UN and now the UK's Minister for Africa, Asia and the UN, Lord Mark Malloch Brown continues the discussion started by Alex Evans of the Center on International Cooperation at NYU

Formerly No 2 at the UN and now the UK's Minister for Africa, Asia and the UN, Lord Mark Malloch Brown continues the discussion started by Alex Evans of the Center on International Cooperation at NYU

Thank you. And I'm glad you're still, even as we get into July, getting such good audience[s] at events like this and I think it shows the concern we all feel about this in a way perfect storm of issues, which has hit Africa - of food, fuel and climate.

And of course we're not the only ones meeting today thinking about this. There's a G8 meeting going on in Tokyo where these very same issues, in the context of Africa, are also being intensively discussed and I think the good news is there's been a recommitment to the Gleneagles Development Targets, there's been an improved commitment on climate change and there's promise of action on both food and fuel.

So, the organisers, Saferworld, had a good prophetic idea in this meeting because as I

say, we are mirroring what's being discussed on the other side of

the world. And that of course is the first answer on 'What are the

policy implications?' They've shot up the agenda enough to get the

G8, not only in their own meeting but, obviously, in their meeting with

the African leaders as well, to focus heavily on just this agenda.

And let me just tease out a

few short, medium and longer term implications of this – and Alex has done my work for me because he's laid out such a

strong description of the problem; but if we just take in the short

term a couple of the countries we are most concerned about and look

at them through the lens of these issues of food and fuel costs, you

see how much it matters.

In the case of Somalia we're

at a point where the price of rice has increased 350% since January

of last year and that now means that 35% of the Somali population are

in need of food aid. If we take Kenya we've seen a 50% increase in

food prices this year; agricultural production fell following the election

violence; there was 30% lost from the 2007 harvest and an assumption

of a 30-50% reduction in the planting for the 2008 harvest which has

meant that Kenya now has 1.2 million people in need of food aid.

Or, if you take the impact

of higher fuel prices, a country like Uganda which has to import pretty

much everything that it doesn't make or grow itself on that long route

from Mombassa on the Kenyan coast, has seen now an inflation

rate of up to about between 10-12% - which is dramatic, potentially, for

stability there. In Somaliland the price of a 200 litre drum of diesel

fuel was $215 in April whereas it had been $132 a year earlier.

So, as Alex was saying, what you're getting is this pattern of food and fuel increases hitting hard at what had been strong rates of economic growth in much of the region over the last few years. Africa has quite a few food importing countries and obviously the food bill has gone up dramatically. It's got even more oil importing countries, and for a non-oil producer such as Malawi the increases since oil started to take-off - just the increase in fuel costs to the Malawian economy - is something like 3% of GDP which was actually more than debt relief and foreign aid during the same period.

So we're seeing some dramatic 'haircuts' to the strong growth that we were seeing. Obviously that growth was hard-won and as it starts to come down it's going to have a negative impact on development; as always it's the poor who get hit hardest and first.

And we've already seen some of the consequences of these price increases. There've been riots in Somalia, Senegal, Cameroon, Burkina Faso. And we see tensions in places like Nigeria, between the north and south, being exacerbated by this.

So, speaking now as against say six months ago, there is this double phoenix here of increasing food and fuel prices, which are of course interlinked, because so much African agriculture, as global agriculture, depends heavily on fuel not just for the transport costs but also for the fertiliser as well. So we are seeing this turning into a very, very dangerous cycle.

Then of course, you add in, as Alex did, climate change on top of that. We've some pretty dire forecasts of African harvests falling rapidly due to increased desertification and cyclical patterns of drought. And it's not just rainfall falling, with a dramatic increase in the levels of under-nourishment, but it's with a quarter of all Africans living within 100 kilometres of the continent's coast – imagine the impact on them as sea-levels start to rise.

Alex mentioned Darfur where perhaps a little simplistic editorial article by the UN Secretary-General shouldn't disguise the fact that there are very real environmental roots to what's happening in Darfur. It is in some ways a fight between farmers and herders over increasingly less land as desertification and water shortages take their toll.

So across the short and medium term one obviously sees a rising

number of problems being driven by these issues of food, fuel and climate.

But I think it is very important not to sort of throw in the towel and revert to a view that this is going to be a kind of universal phenomenon. For those of us who have been working on Africa for long enough these phenomena are hitting in a quite variegated way.

First, you have a group of oil exporters who are doing very well thank you, out of this - Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Nigeria, obviously, when it can export, when the Niger delta is operating. And you've got countries whose agricultural production is currently increasing and where, in some ways, certain groups in the country will benefit from greater incomes as a result of higher food prices; although one's got to be careful about that because most of the higher food prices is coming from higher inputs.

But nevertheless the farmers of Zambia,

Malawi, Tanzania, Ghana, are probably going to see their incomes increase

as a result of this. And while there are poor subsistence farmer groups

who will be hit as they are able to grow less and can't afford to

supplement it with buying food, in some ways the group who may take

the brunt of this are the urban poor, who will see their own livelihoods

affected by a downturn in the economy and then find that food and fuel

are going to cost them a lot more.

Now, what can we do about all this? Well, I think the steps have to fall into economic, political and governance - or policy and governance.

On the economic side we are seeing very smart responses by a lot of countries at the local level, with or without international endorsement and support.

In Ethiopia the government has started to subsidise grain, it's lifted taxes on foods, it's done a series of things. Similarly in Senegal. Malawi is a well-known example of where it's been subsidising agricultural inputs such as fertiliser in recent years and all of these effects - which are looked at rather disapprovingly often by the international financial institutions, because they are thought to amount to food subsidies - are actually contributing in an enormously positive way, or many of them are, to preserving a degree of food self-sufficiency in these countries which they would otherwise have lost. But obviously it devolves on donors such as DFID and governments such as the UK to make sure that the longer steps are in place as well:

- a serious attack on climate change

- a serious investment in improving African agricultural productivity and the efforts of Kofi Annan through the AGRA Foundation with Gates and Rockefeller

- other initiatives by governments to improve the investment in R&D for African agriculture

- the effort by the World Food Programme to mount a short-term humanitarian food aid effort during this first emergency period

These are all critical responses to this; and the effort by

the World Bank and others to put in place short-term funding to help

countries over this period is critical. [We can come back to it more in

the discussion.]

I do think, and this is the really BIG point I want to make, that if ever a set of challenges put new strains on the quality of African governance it's this. There is nothing like the race to control newly discovered energy resources which have suddenly become profitable because of high oil prices; or the race to make sure that with falling growth the disbenefits don't fall disproportionately on the poor.

All of these require governments with a long-term sound policy agenda who are not just accountable to urban elites or to interest groups or ethnic groups which control them, but governments which feel a real sense of accountability and responsibility to ALL their citizens.

And that's necessary both for short term measures of fairness in dealing with economic issues such as food and fuel prices, and it's critical for medium to long term issues of how countries like Uganda or Ghana - both of which are finding that their previous oil and gas, which might not have been profitable, now are profitable for exploitation - how they bring that energy to market.

How they share the proceeds across

their country will be a critical challenge as to whether they remain

countries with a steady, fairly fair, participatory and inclusive growth

model, or whether they slip towards the model of a Nigeria or an Angola

where growth has been highly uneven, highly unevenly distributed and

considered highly unfair across the societies as a whole; where growth has thus become

a source of massive political instability and resentment rather than

a source of investment in the country's successful development.

Above all, you need good governance to tackle the longer term problems which run beyond just the next election cycle:

- climate change

- the investment in re-forestation in Africa

- the investment in really getting the will in place to move to a low-carbon economy when you've only had modest gains from a high-carbon one

These challenges require a huge act of political statesmanship across countries, a willingness to have a long term vision for the future even if there is quite a lot of short term pain in order to deliver on that vision.

So I would argue that these new threats, coming just as growth was in much of the continent getting onto a very nice and stable path, is going to challenge the governance reforms that have been underway in the continent.

If we can see democracy prevailing - and we've seen quite a few political elections this year that have put democracy in balance and on trial in the continent - and even more than democracy, the kind of long term pro-poor inclusive governance which puts the interests of all people, majorities and minorities into a sensible frame; then I suspect Africa can see its way through these problems.

They will certainly have an impact on growth but they need not, in my view, unseat the generally strong political, economic and social changes which are currently characterising much of the continent.

This is a slightly transcript of a talk given in Westminster to the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Conflict Issues on 8 July 2008.

With thanks to Lynn Burke for the transcription.