Welcome to the ezine produced by SGI Buddhists that prompts the positive, kindles the constructive, highlights the hopeful and leaves you feeling - well, up!

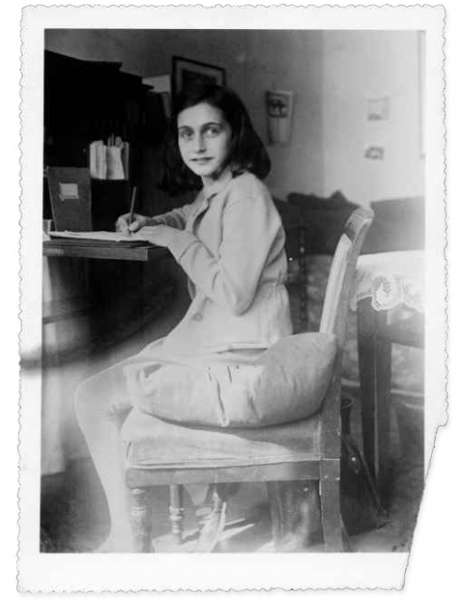

Anne Frank would have been 80 this year - her diary still has a message for us all says Alex Canfor-Dumas

Anne Frank would have been 80 this year - her diary still has a message for us all says Alex Canfor-Dumas

To the casual passer-by there may seem nothing remarkable about 263 Prensengracht – a four-storey building which overlooks a quiet Amsterdam canal. Yet, almost every day throughout the year, a crowd of people gather outside this address, and patiently wait their turn to climb the steep stairs that lead to a secret annexe at the top of the house. Here, more than sixty-five years ago, a young Jewish girl wrote a diary so remarkable and moving that its impact is still felt more than six decades after her death.

When Anne Frank went into hiding

with her family and four other adults in the summer of 1942 to escape the round-up

of Jews in Nazi-occupied Holland, the first thing she packed to take with her

was a new diary – a present for her thirteenth birthday a few weeks

earlier. For two years she meticulously

chronicled the lives of the eight people who were crammed together, day after

tedious day; all of them very different, but all of them subjected to the same

persecution simply because they didn’t fit the Nazi ideal of what a human being

should be.

Unable to venture outside or make any noise during the day, the secret annexe was both home and prison, and for Anne her diary became a means of support and comfort and a ‘best friend’ in which she could confide her thoughts as she had never done before. And in a sense, that’s lucky for us, because today her diary stands as an enduring document against adversity and persecution.

Expressive, lucid and perceptive, it reveals the problems of growing from adolescence to maturity under the oppressive and ever-critical eye of seven other people, as well as the ‘almost unbearable, ever-increasing pressure’ of being in hiding and the constant tangible fear of being caught. But what emerges too, is a young person of immense courage, humour and humanity who, through her suffering, develops wisdom, tolerance and fortitude. “I have lots of courage”, writes Anne after eighteen months in hiding; “I always feel so strong, as if I can bear a great deal.”

Maybe the reason that the diary

of Anne Frank has sold over twenty-five million copies in fifty-five languages

and has never been out of print, is that it has the timeless and universal

capacity to inspire us – even in the face of adversity. We identify with Anne Frank. She is both ordinary – irritable and

stubborn with a longing for boyfriends and nice clothes like any teenager – but

also extraordinary in her unquenchable spirit to hope and dream and to believe

in the future.

Locked away from the madness of the outside world, she was able, nonetheless, to keep intact her strong vision – not only for her own future, but also for a better world. In a famous and often quoted passage from the diary, she writes, just days before the group’s discovery and arrest by the Gestapo: “It’s really a wonder that I haven’t dropped all my ideals because they seem so absurd and impossible to carry out. Yet, I keep them, because in spite of everything I still believe that people are really good at heart.”

This vision, which Anne Frank maintained throughout her two years in hiding, is a conception shared also by Nelson Mandela who was imprisoned by the South African government for twenty-seven years, fundamentally because of the colour of his skin.

For most of his time in prison, Mandela had only sporadic clues to what was happening outside, and to the chain of events that would gradually mobilize the world to release him to become President of South Africa. Yet in all that time, he never lost his vision that apartheid would be dismantled, and continued to fight the prison authorities for the basic human rights of black prisoners. He says of that time: “For us, such struggles – for sunglasses, long trousers, study privileges, equalized food – were corollaries to the struggle we waged outside prison. The campaign to improve conditions in prison was part of the apartheid struggle. We fought injustice, no matter how large or small, wherever we found it; we fought it to preserve our humanity.”

For Nelson Mandela and Anne

Frank, it seems, the courage to endure their persecution was fuelled by the

vision to create and live in a more humane society. Again, Anne Frank writes in her diary: “I must uphold my ideals,

for perhaps the time will come when I shall be able to carry them out.”

Although she died in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945, her legacy – the impact of he words – has survived as a flame so strong that the torch has been handed down through the decades to inspire others, including the then future President of South Africa. During his time in Robben Island Prison, Nelson Mandela and the other inmates read and re-read Anne Frank’s diary, until the sole copy fell to bits. The young girl who wrote, “I want to go on living even after my death!” could never know how true these words would become. Rabbi Hugo Gryn, himself a holocaust survivor and friend of Anne Frank’s father, Otto, has described the diary as “a timeless testament to the goodness of the human spirit as well as to the destructive reality of evil.”

But what is this ‘evil’ that stands at the heart of prejudice and persecution? Perhaps one aspect of prejudice is ignorance; a kind of blindness to the ‘connection’ that exists between human beings, and that our similarity – our basic humanity – far outweighs our superficial differences. Enclosed in our exclusive little groups and ‘isms’, less and less are we able to see the ‘connection’ between all of us and the fact that we actually need each other for our happiness and survival.

Brian Keenan, who was held hostage in Beirut for over four years in the late 80’s, has acknowledged that he owes his preservation – and sanity – to the presence of another hostage, John McCarthy. The early part of Keenan’s captivity had been spent in isolation and had been, quite literally, a torture. He says that outside the four walls of their prison McCarthy, middle-class and English, would have represented everything that Keenan, working-class and Northern Irish, detested. Under the extreme conditions of captivity, however, the superficial differences of class and nationality were revealed for what they were – man-made red herrings. They found, in fact, that their unique qualities and diverse experiences became thing to cherish and enjoy in each other, whilst at heart they discovered – as most people would – that they were simply two people with the same desires, hopes and dreams.

It took the hellish suffering of a prison cell for Brian Keenan to dismantle this specific prejudice and to find that what lay beyond it was more than tolerance; an actual enjoyment of all the diversities he saw between himself and another person. The fact that it took such extreme conditions for this to happen suggests that, in everyday life, it’s not an easy thing to do. But it’s not impossible either.

After all, if Anne Frank could write, after years of oppression: “in spite of everything I still believe that people are really good at heart”, perhaps we owe her just one thing: we need to prove her right.