Welcome to the ezine produced by SGI Buddhists that prompts the positive, kindles the constructive, highlights the hopeful and leaves you feeling - well, up!

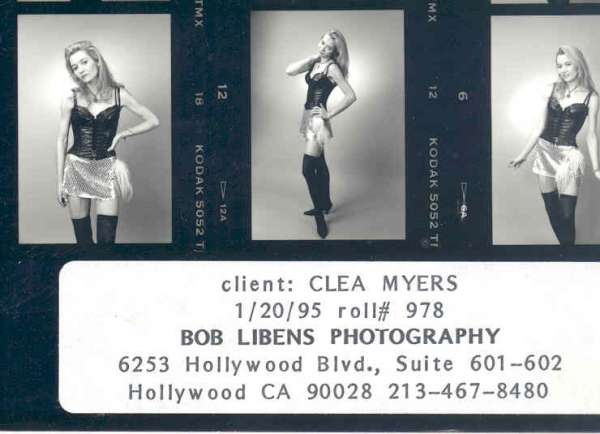

A privileged upbringing, first-class education and burning ambition did not stop Clea Myers from falling foul of crystal meth.

A privileged upbringing, first-class education and burning ambition did not stop Clea Myers from falling foul of crystal meth.

Here she shares her story of addiction to warn others and raise awareness about how devastating this drug really is, before it hits mainstream culture in the UK.

A tweaker is someone addicted to crystal meth, just as a pot-head uses marijuana, or a smack-head is a heroin addict. I became a tweaker in the mid-1990s; I lost everything. I was living in

Under the influence of crystal meth I created a fantasy-world of warped perceptions where I was the star of the movie in my criminal head. LA was awash with sharks and I was one of them. I became rabid to the core, roaming the streets in a deluded and deranged state of paranoia, often times carrying a knife. I almost lost all sense of my humanity and actually did lose my mind. My external life paralleled my inner one that was brimming with confusion, fear and self-loathing.

My life as a tweaker in  from my upbringing in the

from my upbringing in the

My family were not keen on my move to

I became romantically involved with a neighbour, Gordon who was a world away from the ex-public school boys and focused Ivy Leaguers I was used to dating. He claimed to be a found-object sculptor and was ten years older than me. His bohemian lifestyle fascinated me as did his weird group of friends.

The first party he took me to I tried crystal meth, with assurances from him that it was harmless and ‘released your creativity’. I had already dabbled in cocaine at college and discovered that I had compulsive tendencies so I was hesitant. However, the overwhelming euphoria from the drug eased my concern and I vowed to myself that it would be a one-off experience.

Within minutes of snorting it, everyone took on a fascinating dimension and I experienced some kind of release- I felt as if I could be anyone I wanted to be: a creative, artistic and flamboyant soul who would not be judged by anyone. The next few hours were so wonderfully vivid and vibrant; the moment encapsulated exactly why I chose to live in LA.

My relationship with Gordon was unconventional and we never did normal things together like go to the cinema. After a couple of months I realised that his erratic and grandiose behaviour was part of his addiction to crystal meth. I hardly saw him because he was up all night dumpster-diving, while I had a full-time job that I had no intention of jeopardising. One morning on my way out to my car Gordon jumped up on a dumpster, proclaiming and shouting: ‘I’m the King of Hollywood’.

When I got to work I called a drugs help-line for advice on how I could help Gordon. They told me there was nothing I could do until he reached his rock-bottom. I would learn all about this in the not-so-far future.

Soon after Gordon was arrested for bomb-building and the police cleared out his studio. My sense of self-preservation kicked in and I moved to a house-share in Silverlake.

My career became all-consuming. I’d been sponsored by my employer for an H-1 visa and I continued to work for him periodically, while beginning to carve out my reputation as a freelance in film continuity/ script supervising to fund my writing ambitions. I’d written a screenplay about the love between the surrealist painter Max Ernst and the writer Leonora Carrington. An agent at William Morris offered to submit it to various

Paralysed in front of my computer screen, the reality of fulfilling my dream completely overwhelmed me. I was numbed with fear. My inner core did not believe I could succeed. I craved unwavering confidence and the sharp focus in order to rework my screenplay.

In desperation I dug around my belongings and eventually came up with a telephone number for one of Gordon’s friends, who used and sold crystal meth. I called him and arranged to buy some.

I re-wrote my screenplay in a 3-day stretch on crystal meth. My fear of the drug was now replaced with a misplaced respect for it. I deluded myself that without it, I would never have been able to accomplish the re-write. At first one gram, which cost $60, would last a couple of weeks, but within four months, it barely lasted three days.

I started to juggle work with the drug and lost a lot of weight.

I became friends with another crystal meth addict, a 40-year old woman called Marnie. I moved in with her for lower rent than I’d previously been paying and initially we had a great time together. We embarked on a crazy lifestyle of dumpster diving for days on end; this replaced our freelance film work. Marnie and I would drive around endless back alleys with the stereo on full-blast, with Ice Cube or Public Image Limited, scouring dumpsters for junk. She had refined it to an art form and could refurbish anything and re-sell it to shops.

We’d take crystal meth every few hours, and on our drug induced high could stay awake for four or five days, before crashing out to sleep for two days.

After four months, I started disappearing for days on end on my own, dumpster diving further a field and in my own little world that did not include her. Marnie confronted me about being out-of-control and suggested I get help. I told her to go to hell and she kicked me out.

By this point my literary agent informed me that she’d not found a buyer for my screenplay; she encouraged me with a couple of my ideas and I promised to drop off some new work within the next six months. If only. . . now my life tipped over into freefall.

With no job, no home and borrowed money, I moved into a shabby studio near a strip-joint in Sunset, the worst area in

Life in

I would go into a bank all dolled-up with my fraudulent cheques, while they waited in their car outside. On my third attempt, I was arrested and carted off to a police cell while Zed and Tony drove away.

Coming down from crystal meth, starving hungry, dehydrated and locked in a police cell, I was disgusted with myself. Surrounded by aggressive junkie-hookers I was also scared, never having been arrested before. I was charged with cheque fraud and possession of drugs.

As a first-time offender I was given ‘Diversion’ which means I had to prove I was in a Drug Addicts Recovery Program, and pay a fine. By this time I was in contact with my American cousins who supported me through this process. My relations with my parents had disintegrated and I was very ashamed of what I had become involved in.

I agreed that rehab was necessary and I checked into Promises for a six-week stay, kindly paid for by my American family. I gained a crash-course in addiction, an eye-opening experience, as well as benefiting from extensive therapy.

Afterwards I moved into a ‘sober-living’ house for three months, with other recovering addicts. I had major depression, which is the main withdrawal symptom of crystal meth. I regularly saw a psychiatrist and took Anti-depressants that were not very effective. While my life started to fit back together, my denial also started to re-emerge and I decided to try some ‘controlled use’ of crystal meth. Of course, this was total insanity, but I just was not ready to forsake drugs and give up that search for the elusive high.

Back in the outside world, I became fully addicted within weeks, wallowing in victim mentally. I moved into a one-bedroom apartment in Beverly Hills Adjacent. I joined a Models Agency and was cast in a Budweiser commercial; this made me believe that I was getting my life back together and I made a few thousand dollars which I spent on crystal meth and covering basic living expenses. I also started acting classes, but these quickly fell by the way-side as my mind could only focus on using and maintaining my supply. Even dumpster-diving had lost interest for me.

expenses. I also started acting classes, but these quickly fell by the way-side as my mind could only focus on using and maintaining my supply. Even dumpster-diving had lost interest for me.

Within four months I was unable to cover my rent, so I moved in other low-life addicts. I’ve lost count of how many people were in and out of that apartment. I pawned, sold or traded everything from leather jackets, clothes, furniture to jewellery. My self-esteem was non-existent and my self-destructive spiral downwards unstoppable.

My mother had given me some money for a down-payment on a car, a beautiful ’69, pea-green Chevy Malibu that was repossessed because I failed to make the payments. I managed to break into the garage’s car-park and steal back my car. They took it back two weeks later. My paranoia and insanity was peaking and the dodgy people I was mixing with exacerbated my fears and delusions.

Again with no car and almost at breaking point, I took the bus to visit a fellow tweaker’s house to score some crystal meth. Once there I was convinced they had a woman locked in the cellar. Desperate to help, I stole a van parked nearby only to be arrested and be facing a two-year prison sentence.

had a woman locked in the cellar. Desperate to help, I stole a van parked nearby only to be arrested and be facing a two-year prison sentence.

I was held at Sybil Brand Penitentiary for two weeks, the worst experience of my life. I was locked in a communal dormitory that housed around two-hundred of the toughest and meanest women off the streets. Losing my freedom and caged with women, who recognised how different I was to them, further threatened my sanity. My family were now using ‘tough love’ and I had to fend for myself.

Fortunately my state-appointed attorney recognised I was not a career criminal, but a pathetic addict in need of help. In court she argued that because I was British it would be preferable for me to return to the

My mother, who lives in

The day before Christmas Eve, my father picked me up from

I was sectioned to the

Ten days later, after sedation, square meals and rest, I was released. I started attending an NHS rehab called The Stimulant Clinic in Earl’s Court, although no one had a clue about crystal meth. I lived at my father’s house in Fulham and underwent private intensive therapy for the next two years.

I felt determined to overcome the hell I’d created and re-fired my dream to become an actress. I re-developed my senses and re-built my life in

I began practising yoga. I embraced the Buddhism of Nichiren Daishonin. Chanting enabled me to tap into my inner-reserves and transform the negativity within me into something positive. I’ve since written a memoir, Tweaking the Dream: A Crystal Meth True Story. It is now available to buy, thereby creating value out in the real world by sharing my experience, strength and hope.

At age 36 I was diagnosed with Premature Ovarian Failure - a very early menopause that means I am infertile and dependent on hormone replacement therapy until I’m 50. Crystal meth radically ages you in a very short space of time, and although on the outside, I appear to have got off lightly, my insides- in my case my reproductive system- have taken the brunt of my drug use. This is a clear consequence of my drug abuse and has caused me a fair amount of unhappiness. Of course, when I first tried crystal meth ten years ago, I’d no idea this would be one of the prices I would have to pay.

My road to recovery has been long and rocky, but I’ve reached a peaceful plateau where I feel happy about myself. I stopped drinking three years ago and accept and understand that my Recovery has to take centre-stage. It is very much a process and not something that happens in one fair swoop, or certainly not in my case.

I believe the solution to addiction is spiritual. From an early age I recall a hole inside me- a vacuum- that was over-whelming. My compulsiveness and impulsiveness showed up in me by the age of 3, as well as attention-seeking behaviour and focus problems at primary school onwards. Scientific research (

Today I try to get high from healthy activities that nourish and replenish me. I practice Buddhism, Chi Gung, write, dance, enjoy simple activities like walks in beautiful countryside and go to various self-help groups for on-going support: A community of recovering addicts is a very healing and empowering experience.

I am grateful that I am here today- living, breathing and creating a life of value. Sadly many addicts will die from this condition. I almost did and I will never forget that.

Both my parents- neither given to praise- have noticed a profound shift in myself. My essence is the same but my attitude is entirely different. I am beginning to understand what genuine self-respect means, and also what it means to treat others with respect and compassion. Buddhist practice is challenging because it destroys illusions, but the rewards are phenomenal.

I’d like to close with the wise words of Daisaku Ikeda (President of SGI):